Weather Services Advance Precision Agriculture

Some estimates suggest over half of growers’ activities are impacted by weather conditions, from field workability to fertility management to harvest timing. No wonder more companies are entering the weather data and analysis space, either with standalone products or by teaming up with other firms’ management and grower platforms.

The data and modeling here are challenging — one expert called weather data “unstructured and complex” — but here is a sampling of what companies are doing to help guide farmers’ and retailers’ weather-based decisions.

Gathering The Data

All companies in this segment draw from large and varied sources of live, raw weather data that can include temperature, precipitation, relative humidity, wind speed, etc. Feeds can come from national — and increasingly, global — networks, public and private. Information is also tapped from radar, meteorological satellites, surface weather stations, rain gauge networks and forecast models.

No one data source can provide the depth of information needed for more intense agricultural use.

MORE BY LISA HEACOX

For instance, radar can show where rain is, but it measures moisture far above the ground. Those totals can differ quite a bit from what actually hits a field, points out Brad Colman, Weather Science Lead with Climate Corp. For its FieldView platform, the company combines the best data from radar networks (NOAA) with “as many rain gauges as we can get our hands on,” he says.

Climate Corp.’s rainfall data feeds come as an average precipitation measurement for a grid of roughly one-third of a square mile. “We then match those grids up to farmers’ fields. We receive our first estimate of precipitation 15 minutes after the hour; then, as more data is received, we update the readings with additional quality-controlled values,” he explains.

In fact, in 2017, Climate Corp. developed a novel method using “machine learning” to more intelligently incorporate rain gauge data into its model. This new method has improved previous issues by more than 45%.

Analyzing The Data

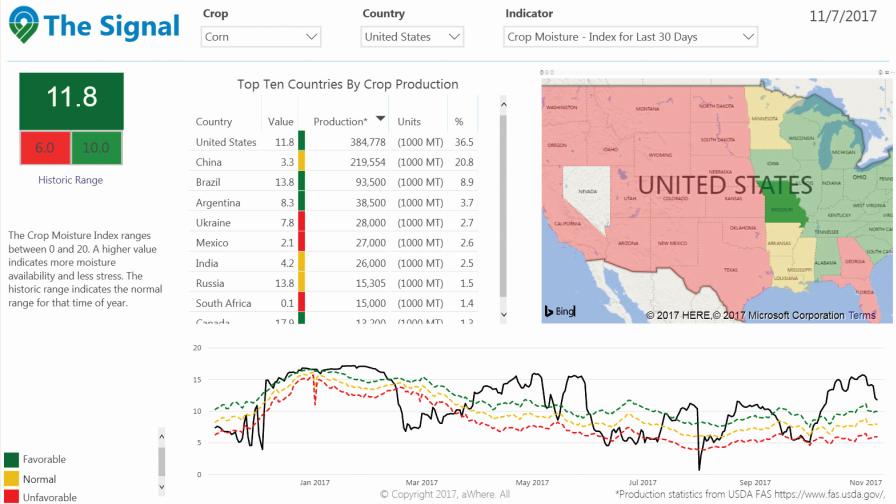

An image from aWhere’s new web-based application, The Signal, showing U.S. corn and the Crop Moisture Index over the last 30 days. Click to enlarge image

aWhere utilizes historical data as well as current conditions in its products. “We have a 10-year history across 1.5 million virtual weather stations worldwide. This allows us to analyze how weather happening today is different versus a long-term normal,” says Brian Soliday, Chief Revenue Officer.

To create those “virtual stations,” the company consumes weather information on a global scale and generates 8 billion data points per day, to basically create a weather-station’s-worth of data every 9 kilometers across the ag earth. “We use soil information and crop calendars as well, so we know where the crop is in its growth stage in a particular growing area,” says Soliday. “If something is happening in the environment (such as moisture stress), we know if it has a potential positive or negative effect on yield or production.”

Soliday sees a huge challenge going forward in the lack of perceived value of weather information, especially when data is so easily available for free via a multitude of sources.

“Weather information is important, but it’s the agronomic insight that we provide that adds real value,” he says. “It’s just a constant struggle for the end user to understand that value and what that means to them on a daily basis — that it helps them increase yields.”

Take a crop stress model, issued daily. Without it, growers look at rainfall and are encouraged that their fields got 15 inches of rain over a growing season, a normal range.

“That may be true, but if the precipitation this year was in three primary events, it wasn’t evenly distributed, and a lot of that ran off. That means the moisture in the soil column isn’t at the level it’s perceived to be,” says Soliday. “Plus the temperatures at night are higher, so the crops are experiencing evapotranspiration and respiration 24/7. This phenomena is not like what we would have seen in years past, where the night cooled down and crop moisture loss would be reduced.”

Joel Wipperfurth, Ag Technology Applications Lead with Winfield United, also sees the problem of charging for weather services, especially because there is a lot of publicly available data. Other service providers need to add contextual interpretations beyond radar and rainfall reports available on the free weather apps on consumers’ phones, he says.

Winfield United actually has weather stations at its 170 Answer Plots to gather data, to use real-time and historically. The company’s research team tracks the trials’ growing environments and generates data to try to predict products’ responses.

“We’re trying to add predictability to the places where the farmer invests,” he explains.

In the Answer Plots, he is now doubling the use rate of weather data that researchers are collecting, using it once to help explain how a hybrid performed and a second time to build a better crop model in the R7 Field Forecasting Tool.

Transferring Expertise

Both aWhere and Climate Corp. service agriculture exclusively, but other companies have entered the ag weather space from other industries.

Expert in the transportation and roadway management industies, Iteris has developed a unique weather and soil data analysis and forecast system specifically for agriculture that helps create a comprehensive, gridded database of atmospheric and soil conditions worldwide. It covers 1980 through 10 days into the future, says Jeff Keiser, Vice President, Strategic Sales and Marketing. The company delivers the information to agricultural companies and product manufacturers through its ClearAg Platform.

Historical data can be important in crop production, Keiser points out. For example, growers may want to compare ClearAg’s five-day forecast of weather and soil conditions to what has happened in the past in their field. Historical data from other sources may come from a station that may be dozens, to hundreds of miles away. That differenceis important, but it may not be clear if the data for both time periods are just presented in a table of numerical values, he says.

Agriculture is one of seven industries that Weather Decisions Technologies (WDT) serves. “Here our approach is to work with companies that are agronomic experts and provide them with the highest quality weather datasets for their platforms, dashboards, and analytics,” explains Richard Reed, Senior Account Executive, Agriculture.

Over the past two years, WDT has developed an answer to the common problem of rainfall on larger farms that have multiple fields spanning several miles. “The most accurate way to get actual precipitation data from the area is to install on-site precipitation gauges, but they can ultimately cost tens of thousands of dollars in equipment and communication costs,” points out Reed.

WDT’s new precipitation analysis system, called SkyWise MetStorm Precision Precipitation Analysis, produces ultra-high resolution (250m2) 1-hour grids of precipitation estimates. There’s no need for in-field equipment.

DTN is known for its vast ag, oil and gas, weather, and commodity trading networks — and has been in the “weather insight” business for 35 years, says Matt Walsh, Vice President Agribusiness. But the company has gone a step further in agriculture by teaming up with partners such as co-ops to offer weather information to retailers’ grower customers.

It has also created DTN Ag Weather Station, an information network that harnesses more than 5,500 weather stations located on users’ farms across North America to report highly local data in real time. “Users have the option of adding their own on-site weather station and aggregating information from their own field,” says Walsh.

The units’ sensors also measure soil moisture, soil temperature, solar radiation and leaf wetness. “This delivers tremendously detailed field-level forecasts and insights for specific areas and geographic regions,” he adds.

Perhaps the largest company doing ag weather these days is The Weather Co., an IBM Business.” As for sheer numbers, the firm’s data platform is one of the largest IoT platforms in the world processing 400 terabytes of data every day from a variety of worldwide sources, serving up billions of forecasts a day globally. “It houses all our APIs and weather data, such as forecasts, observations, alerts and notifications, historical weather data, weather imagery and lifestyle data,” says Chacko Jacob, Agriculture Leader.

The Weather Co. is able to integrate forecasts, soil data, seasonal analyses and current weather conditions into a localized platform that delivers critical analytics for field analysis and crop planting, he says.

More On Soil

Some companies are going below the surface to gather soil information influenced by weather. Iteris has adapted a Land Surface Model with agronomic crop specifications to help generate field surface and sub-surface soil data. This approach goes two meters deep and divides soils into eight unique layers that impact crop production during critical periods such as tillage, seeding, fertilization and at maturity for harvest.

One example of this model at work: potatoes. As a root crop, they take on the temperature of the surrounding soil at the depth they mature. To minimize crop damage and manage crop storage and quality, growers often send out staff with soil thermometers multiple times during the day, says Keiser. One ClearAg user found that the platform’s soil temperature data nearly mirrored the measurements workers made, without trips to the field. The good news is now that grower can plan and schedule harvest operations plus field agronomy staff spend time on more important tasks such as soil testing and evaluating varieties.

Keiser gives other examples where tailored weather information benefits growers. It’s likely that certain seed hybrids or varieties germinate best under warmer soil conditions, whereas others can be successfully planted earlier when the ground is still marginally cool but soil moisture is sufficient.

Then too, some foliar crop protection product formulations may perform best when crop leaves are dry but the relative humidity is on the high side, in order to encourage leaf or stem surface adhesion characteristics, he says.

“These questions tend to modify the paradigm of using weather data from assessing the impact of what happened to the crop due to past weather events to using forecast data to drive business decisions on the most important actions to take next,” says Keiser.

Harnessing Weather In The Future

Experts PrecisionAg® Professional contacted suggested a few technologies that will impact — or be impacted by — advances in weather data.

Hybrid selection. Using reliable weather data, growers will match certain fields or field zones to specific seed genetic characteristics and thereby further increase crop productivity through multi-hybrid planters, predicts Iteris’ Keiser.

New crop protection tools. A whole new class of crop products is beginning to emerge, generally referred to as ‘biologicals,’ he says. These products often are affected by aspects of soil temperature and moisture and have the potential to impact overall soil and plant health.

Robotics. Broader use of autonomous vehicles or robots will be possible thanks to good data on current environmental conditions of both the crop and the field as they vary during the course of the day and the growing season.

Drones. WDT’s Reed says that as technology advances, companies will use drones to collect near-surface weather data over large-scale areas, which will help improve both weather forecasts and operational decision-making.

Remote sensing. aWhere’s Soliday sees a lot more collaboration with remote sensing firms — that offer high resolution satellite imagery or small footprint UAVs — in the future. A weather service platform that indicates stress in a field could direct a remote sensing partner to check it out visually.

“We call that kind of targeting ‘tipping and cueing,’” says Soliday. Growers can see areas they need to focus on and avoid wasting money collecting pixels on areas that are doing well.

Winfield United’s Wipperfurth made an observation about the future of rainfall predictions. Current forecasts begin to break down at the 15-day mark, and meteorologists often look back at data from 15 or even 30 years ago to fill in the gaps. He’s heard there’s a move now to only go back 10 years, because of recent climate shifts. Conditions from just 10 years ago might actually be a more accurate prediction of what’s going to happen with rainfall after 15 days out, he says.