Sensors On The Ground: A Network Of Knowledge

Sensors are certainly nothing new to agriculture. Although they are getting more and more robust, on-board sensors have been providing feedback on the operation of machinery for many years. Liquid tank monitors on bulk chemical tanks have been tracking quantities and sending out the call to manufacturers for refills for a decade. Weather stations have been positioned all across rural America and collecting vital data for some time.

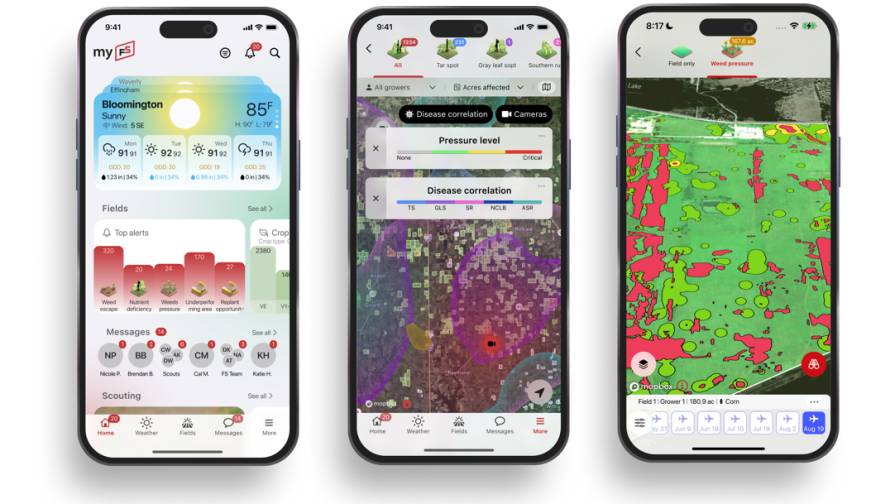

But the advent of wireless connectivity through cellular bandwidth has been a game-changer. Sensors collect data and continuously report back to a data storage receptacle in the cloud, increasing both the quantity and the virility of the data. Phone apps and laptop dashboards pull in data points and provide an easy-to-understand interface that provides feedback in a clear, understandable way.

Sensors In A System

One organization that has worked to push forward as fast as possible on sensor data is Farmers Edge.

“For us, our product is really decision support,” says Ron Osborne, Vice President of Innovation. “We combine a lot of disparate data into our farm command platform, and that data is the underlying information that we use to create analytics and help farmers make decisions.”

MORE BY PAUL SCHRIMPF

‘Future of Food’ Panel Will Deliver Compelling Close to 2022 VISION Conference in January

CoBank Report Asserts Precision Services are Essential to Future of U.S. Ag Retail

Sensors are interspersed throughout the system, and ground zero for data is really the ground. It starts with good, old-fashioned soil sampling with a guy out on a quad or truck pulling cores. Then it gets more interesting.

Farmers Edge maintains what it calls supersites, where weather stations are connected to soil moisture probes and other types of sensing technologies, monitoring characteristics such as nitrogen, moisture, and electrical conductivity.

“We have to connect sensors to weather stations, so we try to consolidate the systems into one data transport layer through the cellular backhaul of the weather station, or through a 900-megahertz network we deploy,” explains Osborne. “In that case, we are combining soil information with weather information.”

The challenge is in the placement of sensors at a farm location that is safe from field activities, but close enough to provide accurate, meaningful data about that particular farm field. “It’s a fine balance to find that location, make the installation, and calibrate it,” says Osborne.

Thousands of Spectrum- and Davis-branded weather stations have been deployed for Farmers Edge, and the system continues to get more robust, he adds.

Farmers Edge also offers machinery data collection via a proprietary telemetry package that is installed on field equipment. “We have about 12,000 machines around the world equipped with our system, encompassing about 90 different equipment brands,” says Osborne. Machines stream in data and provide valuable information on dozens of different field and machine values in real time.

At the end of the day, for Farmers Edge the key pieces of data are soil chemistry, field activities, variable-rate seed, fertilizer, and yield data. And machine info is as important as data files, as it helps the farmer understand and improve productivity. Mix in satellite imagery to help create and manage zones and monitor in-season crops, and Farmers Edge believes it has the closest thing yet to a complete precision package.

“I think we found a sweet spot,” says Osborne. “Scalable technology combined with on the ground experience — that is what farmers need.”

Irrigation Control

Existing ag technology manufacturers as well as a slew of newcomers to the industry have rushed into the sensor business in hopes of delivering the next big thing for agriculture. One area that’s developed rapidly in response to concerns about water availability and quality has been irrigation.

Wireless telemetry and improved soil moisture and weather monitoring have led to the development of a number of systems for farmers and professionals with responsibility for irrigation. Irrigation pivot manufacturers have led the charge in developing the base systems, and one of the leading decision-facilitating dashboard tools is Field Commander from AgSense.

In its most robust form, the Field Commander package allows users to remotely monitor and precisely control center pivots and pumps, along with monitoring flow, pressure, and weather, says Steve Sveum, Vice President, Sales and Marketing. Capabilities include variable-rate irrigation and custom prescription programming, and soil moisture monitoring can also be added.

IRROmeter, another long-time player in the ag irrigation industry, recently introduced a solar-powered wireless soil monitoring system called IRROmesh. Capable of in-field measurement of soil moisture, temperature, and other parameters, sensor data from each system node is routed through an interactive mesh network, then centralized to the web for uploading to a PC or mobile device.

The payoff for irrigation control has proven out, says Tom Penning, IRROmeter’s President. “The benefits of irrigation scheduling based on proper interpretation of soil moisture data are primarily increased yield and quality,” he explains. “Other influences are water savings, labor savings, fuel savings, fertilizer savings, and pest and disease mitigation. Typically most users find the equipment cost recovered in the first season of use if using manually read devices. If automated data collection is involved, then the return on investment takes a little longer.”

Big Plans For IOT

Relatively green Internet of Things (IoT) player infiswift is in the midst of its sophomore campaign after the Bay Area-based enterprise solutions provider incorporated just over a year ago.

Will Shippee, Senior Director of Sales and Business Development, says the company at the moment is focused on working with OEMs and technology providers in the agriculture vertical (infiswift also has customers in the distributed energy field.). Its IoT platform and professional services for precision farming is an “umbrella” for all of its work within the ag industry.

“We’re a technology enabler,” Shippee says via phone from the company’s San Ramon, CA, offices. “Let’s say, for example, a sensor manufacturer comes to us, it doesn’t matter what they’re measuring, be it pH, soil moisture, or whatever it may be.

“So, they come to us and they say, ‘We want to drive a new generation of connected sensors, where we can have from two to 2,000 of these sensors out in a field, and we want them to communicate amongst each other, but also provide various controls, functions, or rules combined with other technologies, say flow pumps or other hardware devices out there.’

“What we would do,” he continues, “is we’d evaluate exactly what those requirements are that the customer wants to achieve, and then we would work with them to advise the right hardware — this can be a printed circuit board and a chip that’s the size of your pinky nail — and that will be deployed amongst each sensor to enable not only the communication between these sensors, but also our embedded software-stack, logic, and business rules that are unique to what the customer wants to achieve.”

Infiswift sees the precision agriculture market currently in the midst of a shift in capabilities, from Precision Agriculture 1.0 (cloud-based storage, datalogger and cell modem-enabled data transfer) to the oncoming Precision Agriculture 2.0.

“What we want to do is break down a lot of those data silos. Rather than relying on capturing data and sending it up to the cloud via cell modem, let’s apply unique, IoT-based solutions to the problem,” Shippee argues.

By applying in an MQTT-based (lightweight messaging protocol) solution around the data, devices can share the data or send it to the cloud depending on what the user requires. Shippee says this MQTT protocol approach allows infiswift to drive down computing power requirements and associated costs while driving up communication capabilities in low-bandwidth areas.

“If you’re pulling data from one type of sensor and you really want that to be integrated with, for example, a meteorological feed from NOAA, we’re able to then pull that data in from that third-party server and then provide your own cloud-hosted architecture. From there, you will be able to pull in that third-party data along with the data you’re generating in your own operations, and drive actionable data off of that.

“We don’t want to just give you ones and zeros, we want to give you actionable data that results either in an efficiency increase or some kind of cost savings.”

Although Shippee declines to name specific companies in agriculture that his outfit is working with at this time, he agrees it’s situations such as the one found in his home state of California, where a statewide farm worker minimum-wage increase has producers antsy about the future, that will drive operations to look more closely going forward at the adoption of automation.

“That really dives into the broader need to increase efficiency in the face of a lack of resources, and a lack of eyeballs on an operation,” he says. “The question is, do you have John go jump in his pickup and check on X, Y, and Z, and then radio back if it’s good? Or do you take that operational knowledge and apply it to those needs, automate that process, and then drive learning off of that moving forward — so John can spend his time managing other things?”